The Incentives of Esports

a ludicrously candid essay

Author’s Note

Hello there!

This essay is my white whale: mapping the incentives architecture of esports, how they’ve gotten the industry to a chaotic status quo, and how (specifically) the industry will need to innovate to move forward to brighter days.

I’m a Riot Games alum who in a previous life ran day-to-day operations for its flagship League of Legends esports product in North America (LCS) and have since worked with a wide range of clients from NBA teams and family offices to game publishers and blue chip brands about video game marketing, particularly esports and content creators.

I’ve condensed years of working experience, hard-won learnings, and candid conversations with industry decision-makers and line workers all into one piece. It’s one of the longest essays I’ve ever written, but I couldn’t do the topic justice any other way.

This piece is divided into two parts: Part I frames the incentives and challenges, Part II is about solution spaces.

I hope you enjoy!

– Avi

Intro

”Show me the incentive and I’ll show you the outcome.” – Charlie Munger

Esports is an emerging industry with exciting products but lackluster business models.

Much of the hype and controversy around runaway investment in the esports industry in recent years stems from confusing the ability to fill stadiums and draw impressive viewership with the ability to cultivate sustainable, large-scale, independent businesses.

To many this may sound like a failure of imagination if not an impossibility. How can products that attract so much viewership and sell out arenas1 possibly struggle to generate scalable, sustainable value for everyone involved?

The short answer is that popular esports are built on top of existing video games that are definitionally2 even more popular and already have existing, robust business models which overshadow the upside that could reasonably be expected from esports revenue as it exists today.

The fact that esports are companion (rather than standalone) products results in distorted incentives for all major stakeholders in the industry.

Let’s put esports in context. The total global esports industry generated roughly $1.3 billion last year, with Asia accounting for more than half of that.3 Reaching the $1B mark is a solid achievement. However, it’s worth keeping in mind the scale of the underlying video game titles esports are built on top of:

Fortnite4: $5.8 billion (2021)

Call of Duty5: $3 billion (2020)

League of Legends6: $1.75 billion (2020)

Counter-Strike7: ~$600+ million (2022) [Editor’s note: Since publication I’ve been told privately the number is far higher. Take this as a very low estimate.]

Free Fire8: $440+ million (2022)

And of course we’re talking about a parent industry that is simply gigantic:

These are some of the most valuable entertainment properties in the world, several of which generate more revenue by themselves than the entire global esports industry in aggregate.

Imagine a world where selling basketballs is ~100x more lucrative than the NBA, and basketball maker Wilson owns the underlying IP of the sport. The NBA has to revshare when they broadcast basketball games and lobby Wilson if it wants to make any rules changes to the game. If Wilson ever decided to not renew the NBA’s basketball license, the league would be toast9.

That’s a close-if-imperfect analogue to where most esports are today. In such a world the NBA would have very different economics and be much less in control of its own fate.

Just as the NBA, Steph Curry, and RDC World share connective tissue in the basketball ecosystem while having different incentives, so too do publishers, pro players, and streamers/YouTubers.

The last decade for professional esports has seen a spectrum of publisher approaches to building a competitive gaming ecosystem.

These experiments have been seeking to answer many questions, but from a business perspective three in particular have loomed large:

Are esports ecosystems basically loss-leading marketing programs meant to delight players and drive engagement and retention in video games? The gaming equivalent of Costco rotisserie chickens?

For the overwhelming majority: yes. However, there are exceptions!

If esports can become sustainably profitable entertainment products, can they also grow to a scale comparable with top-tier traditional sports like football and basketball?

In the long run it’s possible, but it’s also a bit of a trick question: traditional sports are a misleading business analogue for esports since individual video games generally don’t have the longevity of sports.

Of the esports that can scale to that level, is it realistic for third parties to expect meaningful participation in the upside alongside publishers?

It depends on how you define the upside. Esports-specific upside? Yes, there’s plenty of precedent there. Upside in the underlying video game? That’s an uphill battle to say the least.

The early returns are in, and they strongly suggest that much of our conventional wisdom about esports is probably wrong: sustainability doesn’t lie on the other side of simply mimicking traditional sports products like the NFL or NBA, nor by doubling down on esports as marketing to justify more revenue share from video games.

We’re going to answer all of these questions and more, but first we need to set the table: how the esports industry operates, where it generates value, and what the incentives of its major stakeholders are.

Correctly mapping the incentives of key actors is crucial for identifying realistic ways forward rather than getting bogged down in wishful thinking or bag-pumping narratives, both of which have contributed to this latest cycle of hype and collapse.

Third parties essentially building sandcastles on publishers’ private beaches has not proven to be a great recipe for generating sustainable returns, but alternatives that don’t align with publisher incentives are just talk.

Let’s kick it off by examining the most common analogy about the industry: that esports are the natural digital extension of traditional sports.

ESPORTS VS. TRADITIONAL SPORTS

The typical explanation for why esports should look to traditional sports for how to professionalize and scale goes something like this:

Esports are sports–it’s literally in the name! You’ve got world-class pros competing in front of cheering fans to determine who’s the best and raising a trophy at the end. That’s literally the exact same dynamic as basketball, football, etc. Esports currently monetize fans at a much lower rate than traditional sports do, but if they can catch up to their analogue siblings the industry can compete with FIFA/NBA/NFL in the not-too-distant future.

While there are many 1:1 similarities between traditional sports and esports on a product level (fans chanting in arenas, trophies, referees, etc.) from a business perspective they are crucially distinct.

Blurring the similarity in product characteristics with the differences in business incentives is where many smart people get tripped up when drawing comparisons between esports and traditional sports.

There are many ways that the business conditions for esports and traditional sports are distinct– way too many to list here– but two in particular stand out: lifespan and the publisher incentive to prioritize the interests of a game over an esport.

LIFESPAN

“Consumer preferences for games are usually cyclical and difficult to predict. Even the most successful games remain popular for only limited periods of time, and this popularity is increasingly dependent on the games being refreshed with new content or other enhancements.” — Activision Blizzard (Form 10-K 2022)

This is the big one.

The pace of fandom change in traditional sports is measured in decades or even centuries, while in video games it’s measured in years, if not months. It’s comparing ocean liners with rockets– both get things from point A to point B, but similarities break down quickly from there.

The time horizon for esports businesses to create value before the underlying game hits a plateau or begins terminal decline is completely different than the dynamic for traditional sports, which makes long-term investment in individual games much riskier.

The single greatest challenge for any esport trying to match or surpass the trajectory of traditional sports goliaths like football and basketball is that it’s unlikely to be popular enough for long enough to build critical mass, cultivate intergenerational fandom, and imprint in cultural consciousness for the long haul.

As well, even for games which don't plateau in the short-term, the endless stream of new games released into popular genres like first-person shooters means the battle for mindshare and relevance with direct competitors is material and never-ending.

–

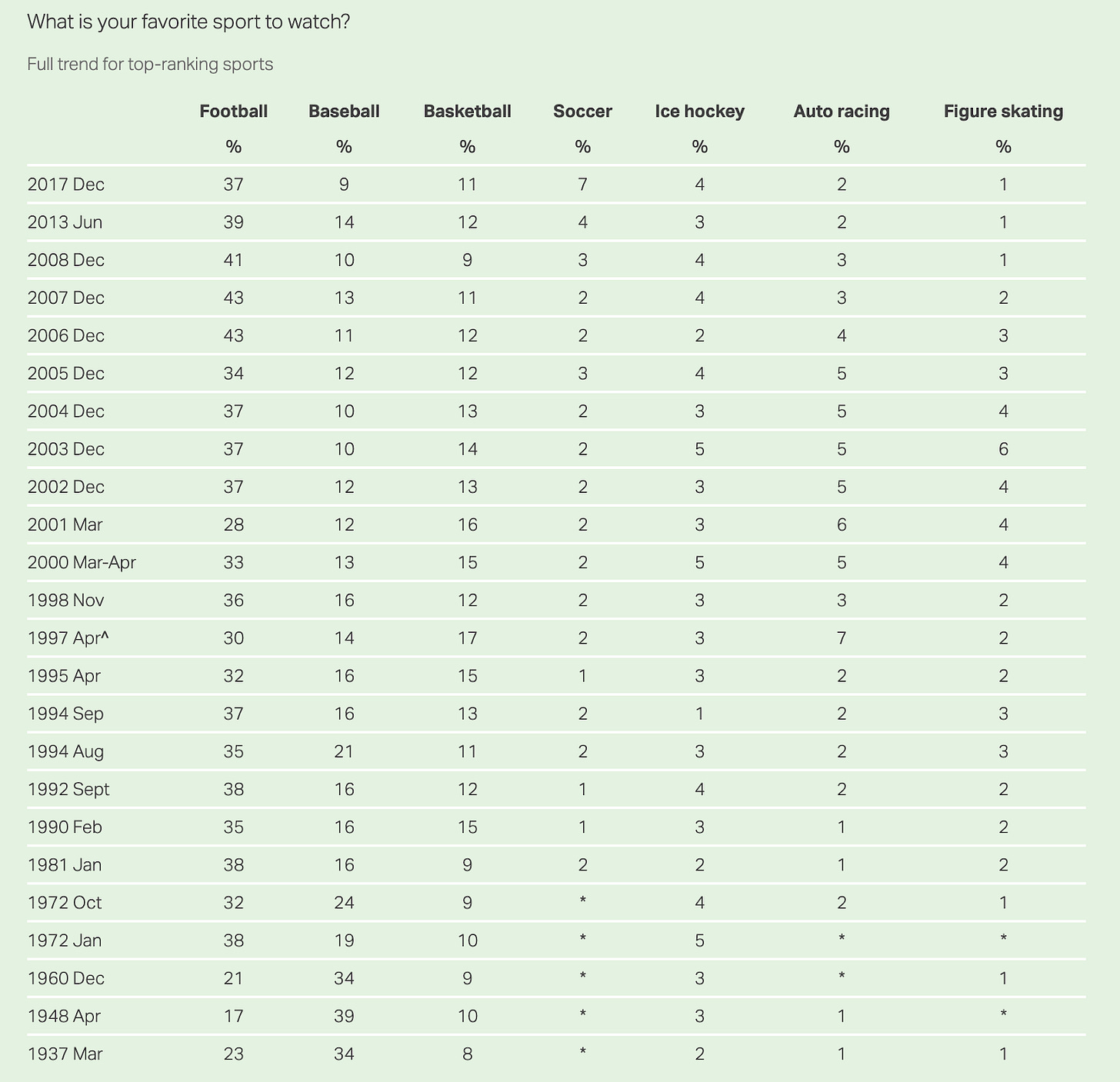

In 2000, the most popular traditional sports in the United States were football, basketball, and baseball. By 2023 they were… still football, basketball, and baseball10.

If we look further back, boxing was extremely popular in 1900 but by 2000 had fallen out of fashion as sports like basketball and football rose up the ranks11. Similarly, baseball had become much less popular relative to football. While there were major trend shifts, they happened over the course of many decades.

Esports looks a bit different.

In 2010 StarCraft II was viewed by many as the pinnacle of the industry after its predecessor had been broadcasting on multiple cable television channels in Korea for years.

By 2013, Starcraft II was grappling with “dead game” memes while League of Legends sold out the Staples Center for its world championship and spun up dedicated regional leagues all over the world.

By 2016, Overwatch was gaining meaningful market share on League of Legends in Korean PC bangs (cafés), an event hailed by some industry observers as a passing-of-the-torch moment. By 2017 it was attracting a stampede of high profile investors from the traditional sports world to join a franchised Overwatch League (OWL) with city-based teams.

By 2018, Fortnite dances were commonplace goal celebrations by FIFA stars and Drake played games with Ninja in an internet-breaking moment. An unprecedented $100 million competitive prize pool was put up for grabs in a Fortnite Competitive ecosystem that rebuffed partnership with esports teams and actively avoided using the word ‘esports’ at all.

By 2020, Valorant emerged from Riot’s R&D lab and immediately began jockeying for pole position with top-dog tactical shooter Counter-Strike, drawing immense viewership on streaming platforms and luring away many high profile CS veterans.

By 2021, the Overwatch League was suffering from low viewership, hemorrhaging sponsors in the wake of scandals12, and by all outward appearances giving up on its highly-touted strategy of playing live matches in city-based studios around the world in a fashion reminiscent of traditional sports13.

In 2023, Valve announced that Counter-Strike 2 was being released with a suite of major updates, resulting in record-breaking player counts14 and strong optimism that one of the greatest esports of all time was starting a bright new era. Several months later, Activision Blizzard announced an upcoming owner’s vote on potentially dissolving the not-yet-decade-old Overwatch League15.

All this to say…

When a professional sports team is weighing whether to lay concrete to build an arena, a critical assumption that makes that investment justifiable is that the sport the arena is being built for will still be popular by the time construction is finished.

If football could reasonably be eclipsed by pickleball which in turn could be overtaken by Calvinball– all within the space of a decade– capital allocation decisions around traditional sports would look completely different.

Though there are a handful of outlier games and franchises that have proven they can sustain competitive scenes over the span of decades such as Valve’s Counter-Strike or Nintendo’s Smash Bros, the overwhelming majority of games begin ramping down in viewership and revenue within a year of release.

We have little idea what a century-old esport looks like because personal computing hasn't been around that long, so there’s forgivable temptation to lean into analogies. However, we should be extremely cautious about drawing 1:1 business parallels between esports and traditional sports given their dramatically different life cycles.

Products driven by short-term incentives tend to develop very differently from ones which have the luxury of optimizing for the long term.

THE GAME WILL ALWAYS COME FIRST

Publishers own the IP of underlying video games which gives them a level of control that doesn’t exist for traditional sports like basketball and football, where inventors do not own the underlying IP.

Combined with the fact that esports aren’t the publisher’s core product, the incentives between players, publishers, and third parties like teams aren't as simple or aligned as “do whatever it takes to increase the size of the [esports] revenue pie” as is generally the case for traditional sports leagues.

Publishers have a finite amount of dev resources and strategic focus, and when there are meaningful trade-offs between an esports ecosystem generating several million dollars in revenue annually and a flagship 10,000 hour game that generates many times that with better profit margins, it’s not a mystery which one the publisher will optimize for.

There are truly countless examples of this, but several immediately come to mind:

Following development of an esports community in Super Smash Bros. Melee, generally considered one of the greatest esports of all time, Nintendo toned down mechanical skill expression in later titles in the franchise. This decision was widely panned by the competitive community and generated significant controversy. Legendary producer Masahiro Sakurai famously responded that top-level competition is simply not at the core of his philosophy for the design of the Super Smash Bros franchise, which is intended to be an accessible party game first and foremost. When asked about this controversy in 2018, Sakurai remarked “I think a lot of Melee players love Melee. But at the same time, I think a lot of players, on the other hand, gave up on Melee because it’s too technical, because they can’t keep up with it... and I feel like a game should really focus on what the target audience is.”16

Overwatch was released as a 6v6 game in 2016 but shifted to 5v5 gameplay for its sequel in 2022, in part to make the game more accessible to casual players by lowering the cognitive load of a match.17 This decision dramatically changed the competitive metagame and more importantly eliminated one starting roster spot for every team in the Overwatch League–yet the change wasn’t voted on by teams or players: they were simply informed what the latest iteration of the flagship product was going to be and expected to adjust. This makes perfect sense from the publisher perspective given that game developers are optimizing for a player base in the tens of millions, not just professional players or hardcore fans of competitive content, but therein lies the point18.

Valve has long been the industry leader of using bundles of in-game goods to fund prize pools such as DOTA 2’s Battle Pass. However, this year Valve announced that they are sunsetting their iconic Battle Pass and more generally de-emphasizing the role of esports in the game’s product roadmap. As they explained in a blog post “Last year, we started to ask ourselves whether Dota was well-served by having this single focal point around which all content delivery was designed… Most Dota players never buy a Battle Pass and never get any rewards from it. Every Dota player has gotten to explore the new map, play with the new items…”

Esports are ultimately companion products— some might call them side businesses for publishers— which means that while opportunity exists to build them into world-class entertainment properties, they face major constraints and instability for which there is no analogue in traditional sports.

So if traditional sports aren’t the right analogue for esports, how about video games generally?

GAMING REVENUE VS. ESPORTS REVENUE

A popular investor pitch about esports over the past decade goes something like this:

The games industry is so big and gaming’s cultural impact is widening every year! If esports can capture just X% of the industry’s output, it will be massive and sustainable. Betting on esports is a bet on gaming– and how can you bet against the long-term trend of gaming?

While there’s a kernel of truth in there, it’s not exactly the right mental model.

It is true that video games are a massive entertainment industry and trending upwards culturally, which definitely is a long term tailwind for the esports industry. However, it’s important to be clear why conflating the overall games industry with esports is a first-order mistake that warps understanding of esports’ total addressable market size (TAM) and incentives as they relate to the games industry.

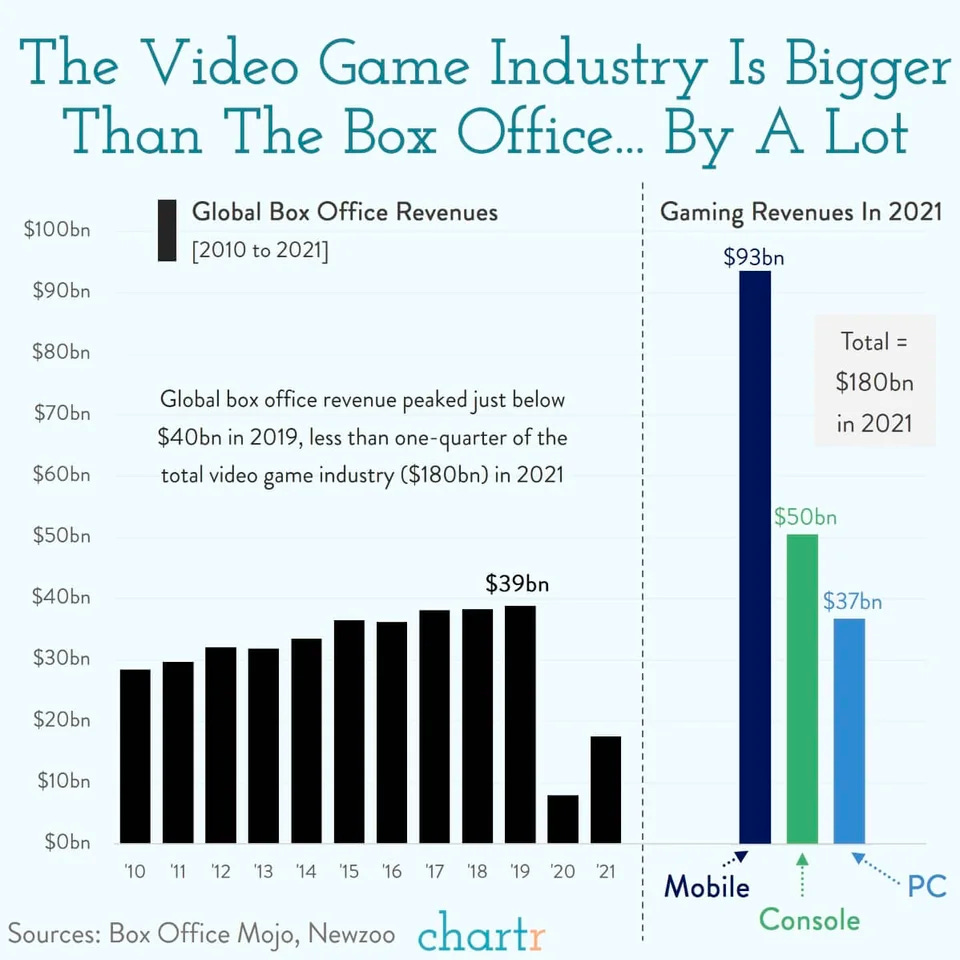

The global games industry is currently estimated to generate north of $200 billion annually19. Esports is projected to account for less than 1% of that20 through direct monetization, which is unsurprising when you consider (1) how few games can sustain esports ecosystems, and (2) the limited nature of direct esports monetization today.

Esports are built on top of a tiny pool of games that are not only popular but have hit a hat trick of wildly challenging conditions, namely that they:

are fun to play

offer competitive multiplayer21 with 10,000+ hours of replayability

are compelling for spectators to watch

This is, to put it mildly, an uncommon achievement.

Esports occupy the very bottom of a gigantic gaming funnel: creating a 10,000 hour game that is competitive, fun to play, and compelling to spectate is excruciatingly difficult and rare to pull off… and yet that’s the minimum requirement for an outlier esports ecosystem to develop22.

If large competitive ecosystems could develop around unpopular games (or once-popular games that have fallen on hard times) that would be a game-changing dynamic for the industry and third parties in particular… but to this point there are no successful examples to point to.

This dynamic frames the perspective of many of the most prominent game publishers of top esports titles, which often23 goes something like this:

Our wildly profitable 10,000 hour game is a golden goose which we prioritize above all else. That said, we care deeply about our IP and are intrigued by the idea of building entertainment properties on top of it, including but not limited to competitive ecosystems to give the IP more depth. We want to make sure that any entertainment properties built on top of our IP adhere to our standards, don’t dilute our brand, and are run with our best interests (e.g. not benefiting competitors) in mind. If you don’t like that, feel free to build on top of someone else’s IP or make your own game.

It’s worth emphasizing: successful publishers of 10,000 hour games tend to deeply care about their IP. Given their high-profile status and use of game IP, esports are an important part of the IP flywheel independent of how much revenue they generate directly . This makes most publishers reluctant to give full freedom to third parties who definitionally don’t have the same long-term incentives and strategic context to steward the IP effectively.

From the publisher’s perspective, the overwhelming majority of value created for games and their esports originate from the fact that the developer/publisher built a game good enough to sustain a vibrant competitive ecosystem in the first place. That belief is well-supported by the overflowing graveyard24 of esports where third parties and publishers tried to force a professionalized ecosystem around a game that didn’t hit the fun-to-play/compete/spectate trifecta.

If esports teams or tournament organizers were able to resurrect a game from the dead or catapult a game from humble beginnings to the top of the charts with esports content, that would change the industry landscape dramatically: truly undeniable value creation that would get every publisher in the industry paying attention.

Unfortunately, no such attempt has yet worked out.

Interestingly, by contrast, there are several examples of gaming content creators catapulting well-designed games from a quiet start to the top of public consciousness such as AmongUs25 and Apex Legends26. That’s a rabbit hole we’ll come back to shortly.

The blunt truth is that it’s just orders of magnitude harder to develop and publish a 10,000 hour video game than it is to run a great tournament or build a strong roster of players. That doesn’t mean there’s no value in the latter, but it drastically weakens leverage and any argument crediting a significant portion of a game’s success to the competitive ecosystem.

The graveyard of unsuccessful games that tried their hand at esports as a marketing strategy is also very crowded– even the most diehard esports fan would readily admit that the magic formula is great game + great grassroots competitive interest. There are no thriving esports ecosystems without extremely successful underlying games.

Third parties commonly respond that esports deliver value later in a game’s life cycle rather than at the beginning: that is, even successful games eventually fade in popularity but esports ecosystems keep them dynamic and engaging to the broader player base by extending their prime, sort of like the gaming equivalent of a Lazarus Pit.

It’s a compelling theory on its face– but is it true? And more importantly: even if true, would it incentivize publishers to actually share more upside with third parties?

So far the answer has been “unclear, but probably not.” Let’s delve into why that is.

/// DIRECT & INDIRECT VALUE ///

As far as value generation goes, esports generate most of their revenue through three mechanisms, which we’ll classify as direct, indirect, and hybrid.

Viewership and attendance of professional competitions (direct)

Increasing engagement and non-esports-specific purchasing in video games (indirect)

Increasing esports-specific purchasing within video games (hybrid)

Direct revenue is pretty straightforward to calculate, and since it doesn’t implicate video game revenue, it’s usually not a hot-button issue. Stakeholder incentives are generally aligned when it comes to direct esports revenue: everyone benefits from an increase in value of media rights, sponsorships, etc. and the revenue coming in is easily attributable to the ecosystem.

Examples of direct revenue include fans paying for offerings such as tickets for live events, merch, concessions, access to gated content or perks, and the like. On the B2B front, platforms (e.g. Twitch, YouTube) pay for broadcast rights, while brands pay to have their products featured in the competitive ecosystem.

Indirect revenue is… not so straightforward to calculate.

Publishers generally focus on player acquisition, engagement, and retention when measuring the performance of marketing strategies for video games. Esports typically provide value by boosting retention and engagement but do little for acquisition, since people unfamiliar with a game are unlikely to follow its hardcore competitive content.

Indirect value generation can play out in a variety of ways. A college student who had previously churned out of the game might be inspired by watching a hype championship finals and decide to reinstall. A teenager might watch a pro player dominate in a tournament using a particular champion and start playing it themselves, and over time buy cosmetics for it. You get the idea.

Attribution for this kind of value generation is generally pretty challenging to measure.

Most games also offer in-game bundles or cosmetics specific to their esports ecosystem, which we’ll refer to as hybrid revenue since it implicates both the underlying video game as well as the appeal of the esports ecosystem specifically.

This brings us to one of the most important and controversial questions in the industry: how much revenue do esports indirectly generate for their underlying video games?

The answers generally look something like this:

“Esports Can Be Standalone Entertainment Properties” Publishers: Esports may have some impact on in-game revenue, but the long-term value is in building new entertainment products that highlight our IP while generating revenue independent of the in-game store. There’s real money and cultural capital at the end of that rainbow, so we’re willing to burn cash in the short term and partner with third parties who are experts at building brands and entertainment/sports properties to get there.

“Esports Is Just Marketing” Publishers: Esports do not materially impact in-game revenue. They’re niche products that mostly appeal to hardcore fans rather than the broader player base. They can be useful engagement and marketing mechanisms, but they’re not a core pillar of our strategy for in-game monetization. Making our competitive ecosystems profitable isn’t a major priority– we’re committed to supporting them and even sustaining losses up to a point, but we’re not interested in unsustainably hyping them up to be more than what they are: marketing programs that don’t need to make a profit to be strategically valuable.

Third-Party Stakeholders: Esports are a cornerstone of video game marketing! They’re crucial for retention and extending the lifespan of games. Publishers get millions in free exposure from esports competitions, and we should get our fair share of that immense value creation.

Stakeholders generally agree that esports deliver marketing value, but there is no general agreement on how to quantify that value.

Game publishers understandably tightly guard specific metrics about their games, particularly those relating to revenue. Data surrounding the impact of marquee esports events on in-game revenue generation may exist, or it may not. If it does, the game publishers aren’t sharing that information externally. This leaves third parties in esports data-blind on how much value they generate for underlying games and understandably mistrustful that publishers are valuing their contributions fairly.

Anecdotally, the broad range of enthusiasm levels among publishers of popular esports titles suggests that the data on how much indirect value esports deliver probably doesn’t point to an obvious conclusion one way or the other. It’s also possible that the impact varies widely by game.

If the narrative that esports generate enormous amounts of revenue that publishers are pocketing for themselves were obviously true, you would expect to see near-universal embrace of esports by publishers, but that’s definitely not the case. Still, only publishers can know for sure.

Calculating how to reward indirect value creation is a high-stakes question between video game publishers and other esports stakeholders because again: the TAM of the video game’s player base is significantly larger than the fanbase of the esport, meaning even mild impact on in-game revenue will typically far surpass what would be a considered a huge win in direct esports revenue generation.

This dynamic often leads to a sort of Dutch disease27 where the easiest answer to increasing esports revenue (just get more revshare from the game!) crowds out focus and innovation on other potential revenue streams, including the most empirically promising path: doing whatever it takes to increase direct monetization, e.g. by making media and sponsorship rights more valuable and the viewership experience more interactive and monetizable.

But is this question a red herring?

Zooming out, it’s important to recognize that publishers have multiple avenues by which to market their games and drive indirect revenue outside of esports (e.g. working with content creators who can expose games to much broader audiences since their content is generally more approachable to players who aren’t already fans of the game), which further complicates resourcing questions and diminishes the bargaining power of external esports organizations and sometimes even publishers’ internal esports departments.

VALUE OVER REPLACEMENT MARKETING

In 2021, popular Spanish content creator TheGrefg shattered Twitch’s concurrent viewership record when he revealed he was partnering with Epic to release his own in-game cosmetic in Fortnite.

It’s hard to overstate the optics of a single content creator’s literal advertisement for a Fortnite skin attracting more viewers to a single Twitch broadcast than every esports event ever broadcast on the platform28, including Fortnite’s own World Cup.

It’s fair to say that Fortnite’s publisher, Epic Games, may have taken note.

Epic is the emblematic example of a world-class game publisher with an iconic 10,000 hour game that made a massive investment into competitive content29, experienced results far short of expectations (missing esports revenue targets by $154 million in 201930), and has subsequently shifted focus31 and marketing dollars in other directions. This includes ramping up collaborations with celebrities like Ariana Grande and LeBron James as well as content creators such as TheGrefg, Loserfruit, and Ninja. It also includes dynamic in-game tie-ins with the owners of iconic IPs like Marvel and Attack on Titan.

Critics can argue that if Epic had made decisions differently, the outcome for Fortnite Competitive could have been meaningfully rosier. While possibly true, a more broadly applicable learning is that even though esports deliver marketing value for video games, they don’t operate in a vacuum: there are compelling alternatives for publishers to invest in.

The general consensus in the games industry has been that by virtue of cultivating direct relationships with their audiences, content creators can generally jump between games with minimal friction and take their viewers with them. As a result, creators can offer great value to game publishers but are less reliable than esports ecosystems, which can’t simply pick up and move to a different game. This is the trade-off.

While somewhat comforting for esports optimists, being the “sure thing” isn’t necessarily the most compelling branding nor does it typically grant much leverage. Esports are generally viewed as one part of a balanced marketing strategy, not outlier secret weapons that deliver more ROI than any other marketing channel.

Esports-specific bundles and in-game items are fairly common in the industry today, but few fans are aware they’re often viewed by publishers as a subsidy for esports rather than a serious money-maker for the underlying game.

Privately, many prominent game publishers have long found it challenging to calculate exactly how much value these in-game tie-ins generate due to the fact that they’re supporting popular players/organizations vs. how much is being generated from the fact that they’re high-quality cosmetics in one of the most popular video games in the world. In recent years, publishers have gotten increasingly candid publicly about these concerns.

Cannibalization of revenue is a serious consideration.

For example, if the publisher of a top esports title releases a Halloween-themed skin for one of their most popular characters32 vs. an esports-themed skin for that same legend, which will sell better?

Turns out that’s a bit of a trick question.

Clearly a skin for a popular hero in a game with millions of monthly active users will sell regardless (and conversely, esports cosmetics in unpopular games won’t), so the more relevant question is actually how many people would have bought a cosmetic for the champion regardless of whether it had an esports tie-in or not.

Some additional questions to consider: in a world where the publisher releases both a Halloween and esports cosmetic, how many sales of the Halloween skin (which doesn’t require a revshare with esports orgs and players, making it more lucrative) would be cannibalized by the fact that an esports skin (which does) is also available? As the ecosystem grows in size, how can a publisher avoid flooding a game with esports tie-in content, especially if there are dozens of teams scattered across multiple regions?

These questions aren’t abstract, nor are the answers universal.

Riot Games recently revealed the impressive stat that three of League of Legends’ top six best-selling skins of all-time are esports-themed (each year Riot creates 1 line of skins honoring World Champions), but that they are struggling to create cosmetics that can move the needle for the other ~100 teams in the LoL esports ecosystem on a consistent basis33.

Meanwhile, Electronic Arts recently made headlines34 over a conflict regarding revenue sharing with esports organizations participating in competitive Apex Legends. After weak sales of team banners (in-game cosmetics less prominent than skins), EA and Respawn reportedly grew skeptical of the value that teams were bringing to the table and declined a proposal by teams for uncapped revshare on skins. In response, one unnamed team executive reportedly said the following:

“So [EA and Respawn are] like, OK, if we make $100 million from this bundle and we’re giving $20 million to the teams, we don’t feel like the teams are going to bring $20 million in sales… From a P&L standpoint, sure, maybe that’s the case. But that’s the problem with them … other developers would say, ‘Maybe the teams are not going to push the sales 20% more than what it would have been, but you know, these teams invest in our ecosystem, they do free marketing for us with them being in an esports programme…’”

Every ecosystem is different and this unnamed executive doesn’t speak for every organization… but talk about out of touch. The cold reality is that publishers care very much about the P&L.

While there can be temporary experimental phases and some indulgence by publishers trying to build generational IP or more absorbed with running a games storefront, there is no long-term sustainable future where publishers are handing out money to third parties without regard for ROI.

A brighter future for esports requires changing incentives to create a dynamic where third parties don’t feel like they’re desperately scrabbling for crumbs that fall from the table of iron-fisted publishers and game publishers don’t feel like they’re working with mercenaries whose main value add is employing players and leveraging world-class IP that they didn’t build.

The urgency around figuring out how to do this has sharpened in recent years as gaming content creators have exploded in popularity, with many capable of consistently drawing audiences that handily eclipse esports broadcasts.

The tug-of-war for resources between different departments responsible for different strategic approaches within game publishers (e.g. creators, paid marketing, esports) is virtually never discussed publicly, but is both common and a powerful signal that if esports has an ambitious future beyond grassroots, it will need to generate a value proposition that’s more defensible/unique than simple marketing for the underlying game, because that lane will always be crowded and competitive.

Yes, in-game revshare is a glittering lure, and should absolutely be part of the business equation. Particularly in ecosystems which are defined by their grassroots or not run with the expectation of becoming a profit center for publishers, revshare on esports-specific cosmetics or bundles can be enough to sustain an entire ecosystem.

However, for ecosystems with ambitions to (1) scale beyond grassroots and (2) be materially more sustainable and independent than typical marketing programs, in-game revenue sharing can’t be the primary load-bearing pillar of revenue. Otherwise, esports will simply be locked into a brutal race-to-the bottom competition for marketing dollars with creators, paid marketing channels, and every other marketing lever at a game publisher’s disposal35.

In that paradigm, when other channels (e.g. working with content creators or paid marketing) can demonstrate higher return on investment than esports, why would a rational publisher not prioritize the higher-performing channels– particularly if they don’t require revshare? How stable can the esports industry expect to be if its primary financial lifeline can change dramatically based on factors totally out of its control?

The key to esports sustainability beyond the grassroots level must be growing esports-specific revenue, because that approach aligns the long-term incentives of all major stakeholders and generates value which is straightforward to attribute to the esports product specifically.

Innovation around fandom and the product experience of consuming competitive content generates value distinct from what creators and other marketing avenues can offer, and in my view is the more defensible path to a sustainable, scalable future.

CONCLUSION

I appreciate you for making it this far!

Let’s quickly recap the major challenges of esports:

Companion Products

Esports are companion (rather than standalone) products which are built on top of incredibly lucrative and difficult-to-build entertainment products: 10,000 hour games. An esport built on top of a game for which there is no organic competitive interest or isn’t popular/fun to play/fun to watch is historically doomed to failure.

Limited Upside and Leverage for Third Parties

This companion product dynamic heavily limits leverage for third parties building on top of these games, and also makes esports a lower priority than the core game for publishers. That doesn’t mean publishers don’t value esports, but that esports are never at the top of the priority list.

Whereas revenue is split 2 ways in most traditional sports (labor and ownership) it splits at least 3 ways in esports: publishers/teams/players, limiting upside for third parties.

Limited Value Over Replacement Marketing

While esports generate marketing value for games, measuring that value is extremely fuzzy. Moreover, there are many other ways that publishers can market their products, several of which readily outperform esports on cost, scale, or even both. The fact that key data-driven publishers of 10,000 hour games like Epic and Valve have been shifting resources away from esports in recent years is a revealed preference that internal data probably does not obviously suggest esports is secretly a major money maker.

Ephemeral Popularity

Video games rise and fall rapidly, which means that trying to blitzscale an esports ecosystem shortly after launch (rather than building gradually on top of grassroots momentum) is extremely dangerous, as Overwatch League investors have learned. Building up a traditional sport is a long term game, building up an esport is the vast majority of the time a short-term one. There are outlier esports that have long-term longevity, but accurately identifying them early has been inconsistent to say the least.

What does it all mean?

Basically, any esports ecosystem looking to overcome these challenges will need to:

Build on top of a generational 10,000 hour game

Cultivate revenue streams specific to the competitive ecosystem to make it clear that the ecosystem isn’t just a loss-leading marketing program but rather a self-sufficient product

Convince publishers to allow third parties to share in the upside of a successful esport with reasonable predictability

Bet that the game lasts long enough to recoup their investment

Many of the biggest bettors on esports over the past decade did not account for these challenges or have a well-crafted strategy for how to work around them.

Is it possible to overcome them?

I believe yes– but very few esports ecosystems can (or should) be fueled to expand beyond straightforward marketing programs for underlying games.

As for the outliers…

Note: only a handful of esports can sell out arenas, much like traditional sports. Most attract small but dedicated grassroots communities that play and watch for love of the game– and for most, that’s enough!

Can a sustainable esport be more popular than its underlying game? It’s certainly possible (see: traditional sports where virtually no one plays contact football after high school yet it’s the most popular sport in America) but there are good reasons to be skeptical (and no current examples in gaming.)

https://nikopartners.com/esports-in-asia-and-mena/

superjoost.substack.com/p/eyes-wide-shut

https://investor.activision.com/news-releases/news-release-details/call-duty-surpasses-3-billion-net-bookings-over-last-12-months

https://www.reuters.com/article/esports-lol-revenue-idUSFLM2vzDZL

https://www.talkesport.com/news/valve-earning-54-million-from-csgo-case/

https://mobilegamer.biz/2022s-biggest-mobile-games-subway-surfers-free-fire-stumble-guys-roblox-and-more/

Matthew Ball has an excellent piece on the macro dynamics of esports that delves into this analogy and the nature of esports from an investment perspective more broadly. https://www.matthewball.vc/all/esportsrisks

https://news.gallup.com/poll/4735/sports.aspx

https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2019/10/29/why-boxing-disappeared-after-rumble-jungle-why-football-could-too/

https://esportsinsider.com/2021/08/coca-cola-and-state-farm-reassessing-overwatch-league-sponsorships

In fairness, while OWL is arguably the poster child of esports excess for the 2017-2023 era, global COVID-19 lockdowns did not create favorable conditions for a strategy built around live events.

https://kotaku.com/overwatch-league-esports-layoffs-blizzard-owl-1850657003

https://www.washingtonpost.com/sports/nintendos-newest-smash-bros-game-showcases-its-odd-relationship-with-esports/2018/07/05/ad8632fe-7568-11e8-b4b7-308400242c2e_story.html

https://www.digitaltrends.com/gaming/overwatch-2-team-size-change/

https://www.dota2.com/newsentry/6252732681186068104

https://www.gamesindustry.biz/video-game-market-revenue-forecasted-to-hit-usd200bn-for-2022

In a sign of the times, the industry’s leading source of revenue projections, Newzoo, announced they were throwing in the towel on esports-specific coverage in 2023 https://esportsinsider.com/2023/03/newzoo-ends-esports-report

Speedrunners, please forgive me

For the purposes of this example let’s define “outlier” as ecosystems which can consistently attract ~100,000 viewers for flagship esports broadcasts.

This is a composite of perspectives I’ve heard from prominent insiders working on the publisher side of the industry. Naturally not all publishers are the same, and Valve in particular is an outlier that doesn’t share this POV given their laissez-faire approach to esports.

There are many examples, though Heroes of the Storm is one that readily comes to mind: https://www.polygon.com/2018/12/14/18141331/heroes-of-the-storm-canceled-hgc-blizzard-community

https://www.pcgamer.com/how-among-us-became-so-popular/

https://newzoo.com/resources/blog/apex-legends-is-one-of-the-best-orchestrated-game-launches-we-have-ever-seen

Economics term to describe the dynamic when a country has one specific industry (usually fossil fuel) far outperform others, which leads to currency appreciation and talent overconcentration in the winning industry, thereby hampering other industries’ growth

Note that certain high-profile esports events are broadcast on multiple platforms (e.g. YT, Douyu, Huya, etc.) and/or allow for co-streaming, which can split viewership numbers.

Between 2018-2019 Epic committed $200M to the Fortnite Competitive prize pool, as well as an undisclosed amount into live events, online broadcasts, and general infrastructure

To be clear: Fortnite Competitive still has a respectable prize pool and gets material support from Epic, but the era of a World Cup at Arthur Ashe Stadium and 9 figure prize pools seems to be in the rearview.

Have you ever noticed how many different terms there are for “character” in competitive titles?

https://www.riotgames.com/en/news/building-the-future-of-sport-at-riot-games

Billy Studholme has an excellent piece on this showdown well worth reading: https://digiday.com/media/inside-the-breakdown-of-eas-revenue-share-deal-for-apex-legends-esports/

Epic Games recently created an innovative revshare program putting 40% of net revenue from the Fortnite Item Shop up for grabs to anyone (including Epic itself…) depending on how much engagement they drive to the game. While esports organizations are free to vie for a share, they have no guarantees or advantages when competing with creators or other third parties for a piece of the pie. https://create.fortnite.com/news/introducing-the-creator-economy-2-0?team=personal. This paradigm smartly sidesteps a lot of the core issues with esports monetization but also illustrates how competition for non-esports-specific marketing dollars is for all intents and purposes a battle royale.

![[Scroll of Strategy] by Avi Bhuiyan](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!j1bB!,w_40,h_40,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F9572cde4-8953-4378-a66f-0537eefaa842_975x975.png)